Saprea > Online Healing Resources > How Does Trauma Affect the Brain and Body?

When something traumatic happens to us, we experience the trauma through both our brain and our body1. We may focus primarily on the distressing feelings we’re experiencing without realizing that our bodies are also manifesting physical signs and symptoms of the emotional response. For example, it is common to experience stomach aches, shallow breathing, sleep disruptions, and lack of focus when we are emotionally distressed, though we may not always realize that our bodies are hurting along with our hearts. Trauma comes in many forms and can be experienced as a result of:

- An accident.

- An illness.

- The loss of a loved one through death or divorce.

- A natural disaster.

- Physical, mental, emotional, and/or sexual abuse.

- Acts of war.

- Being a victim of a crime.

The long-term effects of trauma are often experienced in the small, day-to-day interactions or situations that pile up and cause us to experience toxic stress. Because this trauma can manifest in subtler, quieter ways, survivors may sometimes downplay or dismiss their trauma, believing that what they’re going through doesn’t matter in comparison to another survivor’s challenges. Many may experience the thought, “Someone else had it worse,” or “Someone else deserves help more than me.” We want to emphasize that your experiences and your trauma do matter and that you deserve to find the healing best suited for your journey. Whatever form your trauma may take, it’s incredibly important to learn how that trauma has impacted your brain and body so that you can take the next steps in managing those effects.

How Is Child Sexual Abuse Different from Other Types of Trauma?

One particularly harmful form of trauma is when a child is a victim of sexual abuse. Statistically, the majority of children know their abuser,2 and in approximately half of those situations the child is sexually abused by a peer or older child.3 These statistics highlight the close relationship children have to the person who abused them, which adds to the complexity of the trauma experience (experts often refer to this as betrayal trauma). It is often very confusing to a child who trusts—maybe even loves—someone who is sexually abusing them. Such conflicting emotions may cause the child to question their understanding of the situation, their ability to trust others, and their relationship with their own bodies.

When a child is hurt by someone who is supposed to be protecting them, it is difficult for their developing minds to sort through the experience and make sense of the situation. However, regardless of the child’s relationship to the person who abuses them, every child who is a victim of sexual abuse has experienced a trauma that no child should have to endure. (To learn more about our efforts to help parents and communities reduce the risk of child sexual abuse, visit Saprea Prevention.)

How Does Childhood Trauma Impact the Brain?

One important element of understanding the impact of childhood trauma is to remember that both the brain and body are actively growing and developing during this time. While our brains and bodies continue to change into adulthood, the stages of development during childhood are formative, meaning that our experiences in childhood will carry through to adulthood, and will consequently inform how we feel about our safety, relationships, abilities, and our personal potential.

The brain is a complex organ, and there’s still so much to learn about its functions, abilities, and health. Studies on trauma and its impacts on the brain, however, have helped us understand that there are two areas of the brain that are especially important in working with trauma survivors: the limbic system and the frontal lobe.

Limbic System

Frontal Lobe

What Is the Limbic System?

In the case where fight or flight are concerned, the limbic system will tell our brains to do the following:

- Flood the body with adrenaline.

- Increase the heart rate to pump more oxygen through the bloodstream.

- Increase the availability of oxygen by making the lungs contract quicker.

- Tighten the muscles to brace for a fight or an escape.

All of these changes aid the body in having what it needs to fight or escape the threat. For instance, if you were to walk into a room and notice a large snake on the floor, your limbic system might respond by flooding you with adrenaline, urging your body to jump back in defense, and even prompting you to cry out in distress. The muscles in your legs might tense, bracing to run. Or you might freeze in place, on the off chance that the snake might strike.

Whether the perceived threat is a large snake, a swerving semitruck, or an earthquake, it is the limbic system’s job to communicate to the brain and body what needs to be done to keep you safe.

The limbic system will often go through the same cycle, trying to prepare the body to protect itself from the threat. In situations of sexual abuse, however, the body is often unable to escape. The alarmed limbic system ends up flooding the body with adrenaline that has nowhere to go. Instead, this unreleased stress can remain held in the body while the brain functions in a state of high alert, constantly on the lookout for signs of danger—even when the abuse is not happening. This continual hypervigilance creates a pattern in the child’s brain where their mind and body are nearly always preparing to respond to a potential threat.

HOW DOES THE LIMBIC SYSTEM TRY TO PROTECT ME?

In the case of child sexual abuse, which often goes unreported by the child experiencing it, the brain learns to adapt to the feelings of danger, fear, shame, and confusion by adopting various survival strategies. The brain may block out other information sources to try to process what’s happening. For instance, a child struggling to process the abuse may be unable to focus on schoolwork or other learning (which can have a tremendous impact on academic success).

In other cases, the brain may disrupt the memory of the events, or dissociate all together, leaving the child with periods of time that they won’t remember as they get older. Additionally, the brain may try to protect the body by experiencing physical pain, which can disrupt the hormones in a way that often leads to emotional and mental health challenges. The brain may also learn to associate smells or environments with the abuse, and so as the child encounters similar smells or environments in the future, the brain sends off warning signals (usually referred to as triggers).

Many of these survival strategies become so engrained in the day-to-day actions and responses of the child that they become part of the brain’s go-to system of behaviors and habits (the more scientific term for this is neural pathways, and we explain more about that below).

The brain and body have to prioritize what to process and deal with. As a result, the limbic system prioritizes survival—and we’re glad it does. If you are a survivor of child sexual abuse, your limbic system worked hard to protect you from the trauma you experienced by putting a number of mental, emotional, and physical responses into place. Those responses may have served a purpose in the past but may be hindering you from healing in the present.

For example, to help you survive the trauma of the abuse, your limbic system may have prompted your still-developing brain to dissociate while the abuse was happening. This means that you may have experienced the sensation of leaving your body and watching the abuse from a third-person point of view. This strategy was your limbic system’s way to help distance your brain from a situation that would’ve been otherwise unbearable. But while this strategy was useful—even essential—at that time in your life, it may no longer be the most helpful technique in adulthood. Now, dissociation may lead to you feeling disconnected from your body, detached from your own thoughts and emotions, or unable to fully engage with the present. It may be disrupting your daily life and providing additional challenges to your healing journey.

In the case of child sexual abuse, which often goes unreported by the child experiencing it, the brain learns to adapt to the feelings of danger, fear, shame, and confusion by adopting various survival strategies. The brain may block out other information sources to try to process what’s happening. For instance, a child struggling to process the abuse may be unable to focus on schoolwork or other learning (which can have a tremendous impact on academic success).

In other cases, the brain may disrupt the memory of the events, or dissociate all together, leaving the child with periods of time that they won’t remember as they get older. Additionally, the brain may try to protect the body by experiencing physical pain, which can disrupt the hormones in a way that often leads to emotional and mental health challenges. The brain may also learn to associate smells or environments with the abuse, and so as the child encounters similar smells or environments in the future, the brain sends off warning signals (usually referred to as triggers).

Many of these survival strategies become so engrained in the day-to-day actions and responses of the child that they become part of the brain’s go-to system of behaviors and habits (the more scientific term for this is neural pathways, and we explain more about that below).

The brain and body have to prioritize what to process and deal with. As a result, the limbic system prioritizes survival—and we’re glad it does. If you are a survivor of child sexual abuse, your limbic system worked hard to protect you from the trauma you experienced by putting a number of mental, emotional, and physical responses into place. Those responses may have served a purpose in the past but may be hindering you from healing in the present.

For example, to help you survive the trauma of the abuse, your limbic system may have prompted your still-developing brain to dissociate while the abuse was happening. This means that you may have experienced the sensation of leaving your body and watching the abuse from a third-person point of view. This strategy was your limbic system’s way to help distance your brain from a situation that would’ve been otherwise unbearable. But while this strategy was useful—even essential—at that time in your life, it may no longer be the most helpful technique in adulthood. Now, dissociation may lead to you feeling disconnected from your body, detached from your own thoughts and emotions, or unable to fully engage with the present. It may be disrupting your daily life and providing additional challenges to your healing journey.

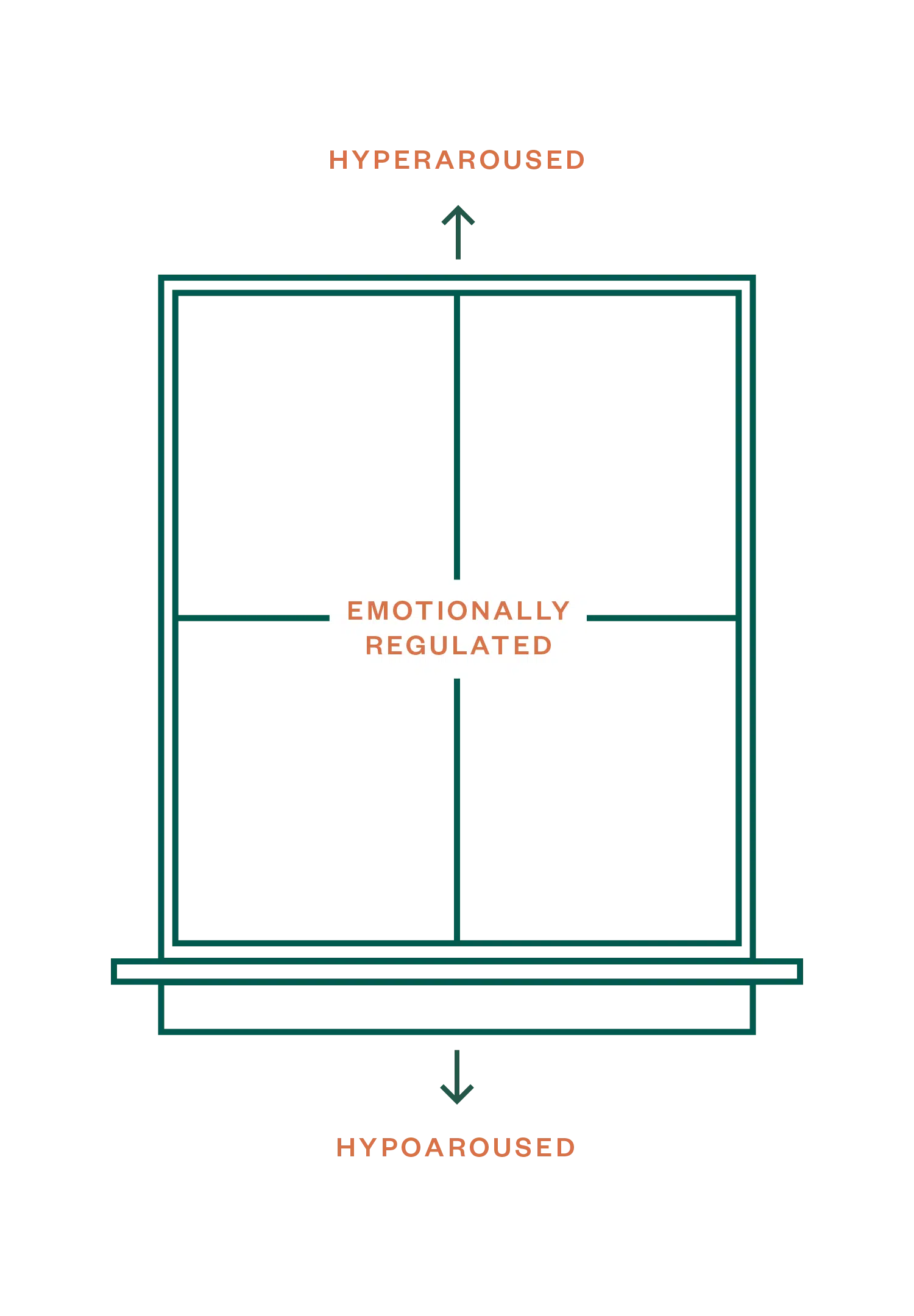

The Limbic System and the Window of Tolerance

Window of Tolerance

Hyperarousal (Fight/Flight)

- Hypervigilance

- Mania

- Out of control behaviors

- Difficulty concentrating

- Self-judgment/self-criticism

- Intrusive imagery/flashbacks

- Quick breathing

- Rage

- Irritability

- Verbal and/or physical aggression

- Arguments

- Need for control

- Perfectionism

- Impulsivity

- Defensiveness

- Rigidity

- Emotional outbursts

- Chaotic responses

- Nightmares

- Physical pain

- Isolation

- Dry mouth

- Shaking

- Anxiety/panic

- Feeling overwhelmed

- Avoidance

- Restlessness/fidgeting

- Sabotaging relationships

- Feeling trapped

- Excessive exercise

- Disorganized thinking

- Misusing alcohol, drugs, food, etc.

- Insomnia

- Obsessive compulsive behaviors/thoughts

Hypoarousal (Freeze)

- Dissociation

- Time slowdown or disturbances

- Shutting down

- Numbness

- Disconnection

- Separation from self

- Going on autopilot

- Physical pain

- No display of emotions

- Memory issues

- Rumination about unworthiness

- Feeling stuck

- Depression

- Hopelessness

- Helplessness

- Shame

- Sadness

- Despair

- Sleeping too much

- Overcompliance

- Paralysis

- Fuzziness

- Isolation

- Exhaustion

- Trouble focusing

- Lack of motivation

No matter what symptoms of hyperarousal and hypoarousal you experience, and to what level those responses are disrupting your life in the present, healing is still possible, which is where the frontal lobe comes in.

What Is the Frontal Lobe?

The frontal lobe is the area of the brain where we employ strategies for evaluating, thinking critically, and choosing action. This is very much the “decision-making” center of the brain. And this part can learn, including learning new patterns of thought, behaviors, and strategies.

For instance, returning to the snake example, the frontal lobe is the area of the brain that would assess all of the information available and come to the conclusion that the snake is fake and part of a practical joke. It would then communicate to the limbic system that there is no need to panic.

The frontal lobe is actively developing in childhood (think about how much a baby changes during their first five years of life) and continues to develop well into adulthood. In fact, research suggests the frontal lobe is still growing into an adult’s late twenties or early thirties. What this means is that the limbic system, which is active from infancy, takes a more active role in responding to childhood sexual abuse; the frontal lobe, which needs much more information, experience, and time to grow, is unprepared to deal with sexual experiences at a young age, much less sexual abuse. (It is for these reasons that Saprea firmly asserts that a child cannot consent to sexual activity, especially in situations where sexual activity is with an adult or older child who is developmentally more advanced.)

What is especially exciting about the frontal lobe (from the lens of healing from trauma) is the opportunity an adult survivor of child sexual abuse has to evaluate, think critically, and choose action. The frontal lobe’s ability to learn new habits, to employ different responses, and to think critically about a situation means that, despite the inability to change the past, we can definitely change our experience in the present and create a more fulfilling future.

What Is Neuroplasticity and How Can It Help Me Heal from Child Sexual Abuse?

Brain science is rapidly developing, and there’s still so much we don’t know. And, at Saprea, we love to talk about the amazing brain and its potential. The brain is able to adapt, grow, and change (often referred to as neuroplasticity), which is great news for trauma survivors.

To better explain neuroplasticity, it’s helpful to talk about neural pathways. Neural pathways are engrained behaviors and habits that become an essential part of the way we act and respond to day-to-day life. Think of it this way: imagine walking through a field of tall grass. The more you walk on a specific area, the more the grass will get tamped down. And if you walk on it enough, the grass may stop growing altogether. If you abandon that path, you have to go through the process of knocking down the grass in the new path. It’ll take time, but eventually you’ll have a new, clear path cut. And if you abandon both of these paths and start a new one, over time the grass will begin to grow again and those earlier paths will be less visible.

The neural pathways in your brain are very similar; the more often you use a pathway, the stronger the brain’s impulse is to use and reuse that same pathway. So, if you use the same route to get to work each day, your brain uses its memory to pull up the neural pathway that automatically knows how to get to work. It becomes so routine, so integrated into what we do and who we are that we don’t even notice that our brains are using neural pathways to help us navigate through life.

That being said, neural pathways can be created for behaviors and habits that serve us well, as well as for behaviors and habits that impede our progress. Triggers are a great example of a disruptive, frustrating neural pathway. With a trigger, the limbic system learned to associate something (a smell, for example) with a traumatic event from the past. And every time the survivor encounters that smell, the limbic system goes down that familiar path and tells the body it’s in danger, which in turn engages the body’s survival response.

This is a very natural response, and our brain and body work together to ensure our survival. But when there isn’t any danger to respond to, the feeling of being triggered is very unwelcome and could, for example, cause a survivor to flee an event or activity where no threat is present and spend the rest of the day alone, struggling with feelings of isolation and shame.

The good news is that, just like the field of tall grass, new neural pathways can be developed and old ones can weaken, thanks to the brain’s amazing ability to adapt and grow. Using the example above, when this same survivor practices a grounding technique (such as paced breathing) over and over again until it becomes a well-worn habit, they can use that technique the next time they encounter a trigger in an otherwise safe space. So instead of running away the next time they feel triggered, the survivor can take deep breaths, slow their rapid heart rate, soothe the panicked limbic system, and remind themselves that they are in the present and out of danger.

These new neural pathways can also strengthen the communication between your limbic system and frontal lobe, which can better work together to keep you safe. Remember, despite how it may sometimes feel, your brain and body are working with you, not against you. Your limbic system is not in any way broken, bad, or something that needs to be overcome or suppressed; rather, it is an essential part of your brain that is doing the best it can to protect you based on the tools that were available when the abuse first began. Now, through the power of neuroplasticity, you can reteach your limbic system to utilize tools and techniques that will be most helpful in serving you as an adult.

How Can I Reduce the Effects of My Child Sexual Abuse Trauma?

Saprea empowers survivors of childhood sexual abuse by sharing tools and strategies to encourage the development of new neural pathways. If you are a survivor of child sexual abuse, you may find it beneficial to practice coping strategies to help manage your symptoms. As you practice grounding techniques, you interrupt the brain’s travels down familiar (but unhelpful) pathways. And the more you practice, the more new pathways will develop and become a part of your behaviors and habits.

So much of the work you’ll do in healing will be focused on intentional responses and thoughts, and it will be helpful for you to understand the benefits of practicing Acknowledgement, Mindfulness, and Aspiration as you work on building a new network of neural pathways.

While you can’t reverse the clock and protect your younger self from having to endure sexual abuse, nor can you take back any unhealthy coping habits that you may have employed to deal with the pain of the past, you absolutely can embrace the hope that you will experience healing. The trauma of the past can have less and less influence on the present because your brain, body, and heart are capable of so much.